|

|

本帖最后由 pedro 于 2012-5-3 23:51 编辑

Barcelona 2-2 Chelsea: Chelsea do an Inter 2010

April 25, 2012

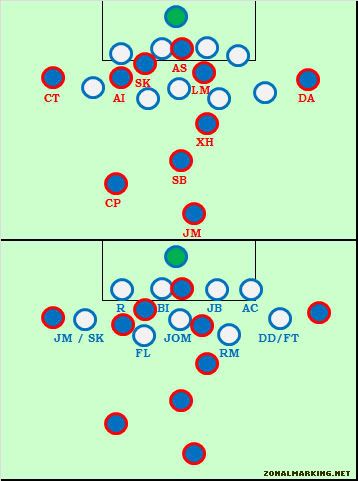

The starting line-ups

Chelsea produced an astonishing defensive display – and still created chances – to progress to the Champions League final.

Pep Guardiola made the surprising decision to drop Daniel Alves, bringing back Gerard Pique in defence. Isaac Cuenca was fielded on the wing, and Cesc Fabregas in an attacking central midfield role.

Roberto Di Matteo named an unchanged XI from the side that won 1-0 in the first leg, and set out in the same shape.

There were two first half substitutions due to injury, however – Gary Cahill went off and was replaced by Jose Bosingwa, with Branislav Ivanovic moving into the middle. Gerard Pique also had to depart, with Alves back in the side and Javier Mascherano moving to the centre of the back three.

Where to start? Like in the first leg, Chelsea had to rely on Barcelona squandering some very presentable chances, but their overall display at the back was excellent.

Barcelona formation

Barcelona’s shape was something like a 3-3-1-3, with Lionel Messi playing as the number ten. Cuenca was used on the right to stretch the play, a reaction to the first leg, when Barcelona lacked true width. He often lost the ball when attempting to dribble past his full-back, though he did provide the assist for Sergio Busquets’ first goal, which came from him staying wide following a corner – in that respect, he did his job OK.

Alexis Sanchez was used through the middle, where he had an instant impact against Real Madrid at the weekend. He combined with Messi early on, and although Messi didn’t have a particularly good game here, at least the Chelsea centre-backs were being distracted by the clever runs of Sanchez, and Messi was getting into good positions on their blind side. Sanchez was also clearly troubling John Terry, shown by his red card.

Chelsea shape

The major effect of Barcelona’s switch to a 3-4-3 was that Chelsea could be even narrower than in the first leg when the ball was in the centre of the pitch, and make a very tight unit that Barcelona found it difficult to play through. Ramires, who had spent the first game running up and down the line with Dani Alves, now had no full-back to track and could tuck in as an extra midfielder, while Juan Mata did the same on the other side. There were also even greater opportunities to break down the line into space – Ramires and Ashley Cole did that in the first minute, but afterwards Chelsea struggled for an out-ball.

Instead, Petr Cech thumped the ball down the pitch for Drogba to chase – an approach that almost worked in the first leg, and threatened a couple of times here, perhaps most obviously when Victor Valdes came out and clattered into Drogba and Pique.

11 v 10

Terry’s red card (in Inter 2010 terms, the Thiago Motta moment) changed things. Di Matteo’s initial reaction was to bring Bosingwa inside along with Ivanovic , and move Ramires to right-back. Chelsea were now 4-4-1, the most common way to play with ten men. But because their approach until then had been to defend with 4+5, they now looked uncomfortable defending with 4+4, even if they’ve been playing that way in the league. The away side were disorganised in the minutes leading up to half-time, and Andres Iniesta’s goal came when the midfield had no shape.

However, Ramires broke down the flank brilliantly for a crucial goal on the stroke of half-time. Ramires had created the goal for Drogba at the same point in the first leg with a similarly-inspired counter-attack, and just as that goal allowed Chelsea to sit back and defend at Stamford Bridge in the second half, they could do the same here.

Second half

When Di Matteo got the players in the dressing room at half-time, he essentially switched back to the way Chelsea had been playing until the red card, defending 4+5, with Drogba out wide on the left – just as Diego Milito had filled in on the flank for Inter in 2010. Therefore, the way Chelsea defended wasn’t actually any different from how they’d started the game…although since they had no striker and no-one to hold up the ball, they had to do much more of it.

They also had players out of position, and the man they may have worried about, Bosingwa, did a fine job in the centre of defence. It’s been discussed before that sides are better off with quick, nippy full-backs in central positions against Messi, rather than lumbering, physical centre-backs. Bosingwa’s job was about tracking and tackling rather than heading the ball clear – Barcelona barely crossed in the air, and Bosingwa wasn’t exposed.

Rough second half positions (same image, different labelling for either side)

Guardiola had changed system for the second half, moving Iniesta inside, bringing Cuenca to the left and telling Alves to push on down the right. Guardiola was trying the classic strategy against ten men – make the pitch as wide as possible. Chelsea adapted by playing wider in midfield – now, rather than the wide players moving very centrally without the ball, they stayed towards the edges of the penalty area. This worked excellently – they never allowed their whole team to be sucked to one side, and Barcelona never had a player on the overlap in a considerable amount of space. Drogba conceded a penalty, of course, but at least he was helping out defensively.

Chances?

The penalty was obviously crucial to the game, and like in the first leg, Chelsea had to rely on poor finishing. There were some who said Chelsea’s approach at Stamford Bridge wasn’t particularly effective because Barcelona had chances, but any strategy against Barcelona will always allow them some opportunities – they’re too good to be kept at bay for 90 minutes.

The key was that Chelsea limited the number of chances they had in the first leg to a reasonable number – around five, at a rough count. That is an acceptable figure against Barcelona – on a bad day you might concede five, but Barcelona do waste chances, so you’re giving yourself some hope.

Again, with a non-scientific counting system, Messi’s penalty was Barcelona’s fifth clear chance of the game. Thereafter, they barely created anything, with long-range efforts and half-chances their only sights of goal.

Barcelona problems

Barcelona had two main issues in the second half. First, they had too many defensive players on the pitch – Javier Mascherano and Carles Puyol as centre-backs, and Sergio Busquets as a holding midfielder. Chelsea were breaking, but when Barcelona had the ball (which was the vast majority of the second half), they had 3 v 0 at the back. Mascherano could have been sacrificed, Busquets could have played his half-and-half role, and still could have played the first pass into the final third. (It’s also worth asking whether playing a back three at the start, comprised of pure defenders rather than Alves or Adriano as half-defenders, was a wise move against a side only playing one striker.)

The second issue was exactly the problem they faced against Inter two years ago – they had no plan B, in the shape of a static central target man to find, either in the air or for some hold-up play. In fact, they had even less of a plan B. Two years ago, Guardiola’s mistake was that he played his plan B as his plan A – Zlatan Ibrahimovic started the game when Inter were playing quite high up, then had been removed by the time Barcelona realised they needed a central striker. At least in that game Barcelona could push Gerard Pique upfront to be their number nine, and although they didn’t turn the tie around, Pique scored a brilliant consolation goal.

Ibrahimovic has been sold, and Pique had gone off injured. Barcelona didn’t have anyone they could look to here, which was probably why Seydou Keita was brought on for Cesc Fabregas, despite the fact Keita is naturally a more defensive player. Admittedly, Keita had little impact (and again, Guardiola could have sacrificed a more defensive player), but the move made some sense.

By this stage Barcelona’s positions had ceased to exist, but the roles were still fairly obvious – three defensive players, Xavi orchestrating from deep, Cristian Tello (on for Cuenca) and Alves on the flanks, then Keita, Iniesta, Messi and Sanchez in and around the box.

Chelsea hang on…

Chelsea continued to be extremely tight in the centre – Lampard, Meireles and Mikel were unmoved despite the tactical changes, and replicated their approach from the first leg. All three stayed central, and when Xavi got on the ball and looked for forward pass, one player often came out to casually close him down – not really attempting to win the ball, but forcing him to play out to the flanks rather than a more incisive ball. Mikel again found himself ahead of Lampard and Meireles when doing this.

The one difference from the Inter strategy was that Chelsea didn’t immediately drop back to the penalty box – in fact, when Barcelona built moves from their own penalty box, Chelsea stayed quite high. It was surprising that Barcelona didn’t seek to play forward more quickly here – their passes were slow and predictable in deep positions, when they really needed to hit Chelsea when their defence was off-balance up the pitch. Barcelona also failed with the majority of attempted dribbles.

…and pounce

Chelsea, remarkably, still managed to offer a goal threat. Drogba was superb and won a corner (something Real Madrid did well at the weekend), from which Ivanovic should have scored. Kalou replaced Mata and found himself through on goal, but wasted the chance.

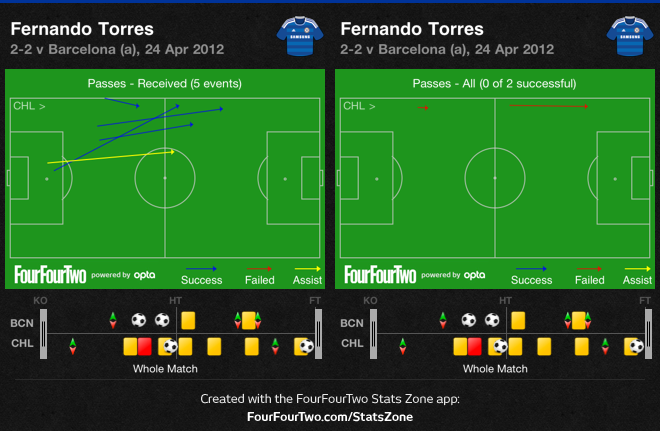

Fernando Torres replaced Drogba late on, and was the hero with a late goal. There was absolutely no natural logic to this – Torres had been far less effective than Drogba on the left, failing to track his man and giving the ball away. In fact, he only found himself through on goal because of a failed dribble that meant he was out of position – Barcelona, having thrown everything forward in the final minutes, were now literally in a 0-5-5 formation at that point.

But in a way it was fitting – the goal came from a hoof downfield from the Chelsea penalty area to the number nine. That was the approach they started with at Stamford Bridge – when Drogba failed to control a punt from Cech when through on goal – and that was the way they sealed the tie.

Conclusion

In Monday’s press conference, Petr Cech was asked if he’d been on the phone to Jose Mourinho, asking for tips about how to beat Barcelona. The question was referring to Saturday’s 2-1 win for Real Madrid, of course, but more appropriate was Mourinho’s triumph two years ago. The situation was almost identical – semi-final second leg, early red card, strikers playing on the flank, ultra-defensive. When two sides have completely different approaches yet contest a close match, it makes for a brilliant spectacle.

Barcelona have won the Champions League twice under Guardiola in similar circumstances (two-goal victories over Manchester United), they’ve now been eliminated twice in similar circumstances (failing to break down a side parking the bus at the Nou Camp). However, it’s worth pointing out that they lost the tie in the first leg as much as in the second, and probably had their better chances at Stamford Bridge. They also failed to score an away goal, which meant Chelsea had a significant advantage after Ramires’ goal.

With many star performers over the two legs it feels unfair to pick out a single player, but Ramires is the ideal player for playing against Barcelona. He is mobile, hard-working and energetic without the ball, but also breaks directly when possession is won. He looks forward, and breaks past Barcelona’s first press. His superb finish was a nice bonus.

The final conclusion is to reiterate a point made last week – the Champions League semi-finals consistently produce the most intriguing, unpredictable games in modern football, and its most memorable moments. |

|